These are OUR lands - and they need us.

Grab a cuppa and have a seat, because it’s story time.

Bison herds grazing the prairies of the American West, showed in a diorama at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Once upon a time, in the 1800s, there was a sickly little boy who grew up in New York City, suffering from asthma and near-sightedness. The precocious child often hung out at the library, where he loved delving into books about plants, wildlife and natural history. But his very favorite place was the outdoors. The fresh air relieved his asthma and every summer, he spent the summers in the countryside, collecting tadpoles, watching bird and sketching in his nature journal. Later, as a young college student at Harvard, he went on a camping trip in the deep woods of northern Maine. Part natural history expedition, part soul-searching retreat, the trip made him cultivate a deep appreciation for the wilderness that hadn’t yet been touched by humans.

In 1883, the young man traveled west to experience true frontier life, pursuing a longtime boyhood dream. He bought a ranch in the Badlands in the Dakota Territory, where he witnessed first-hand the settlers’ mass slaughter of the American bison. The animal, which was at the heart and soul of Native American culture, had once roamed the prairie numbering in the tens of millions, but was now on the verge of extinction. The experience moved him deeply and when he returned to the city, he began to advocate for conservation of America’s wild places.

The “Conservation President”

The man’s name was Theodore Roosevelt, and he went on to become governor of New York. Then, in 1901, he was elected president of the United States. Early in his presidency, Roosevelt went on a three-day camping trip in the Yosemite wilderness with the famed naturalist John Muir, who convinced him to protect large swaths of land for parks from development. He was the first president to prioritize conservation and eventually moved to protect 230 million acres by establishing five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 national bird sanctuaries and wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests.

These lands – and many more – belong to every American. They are also under attack.

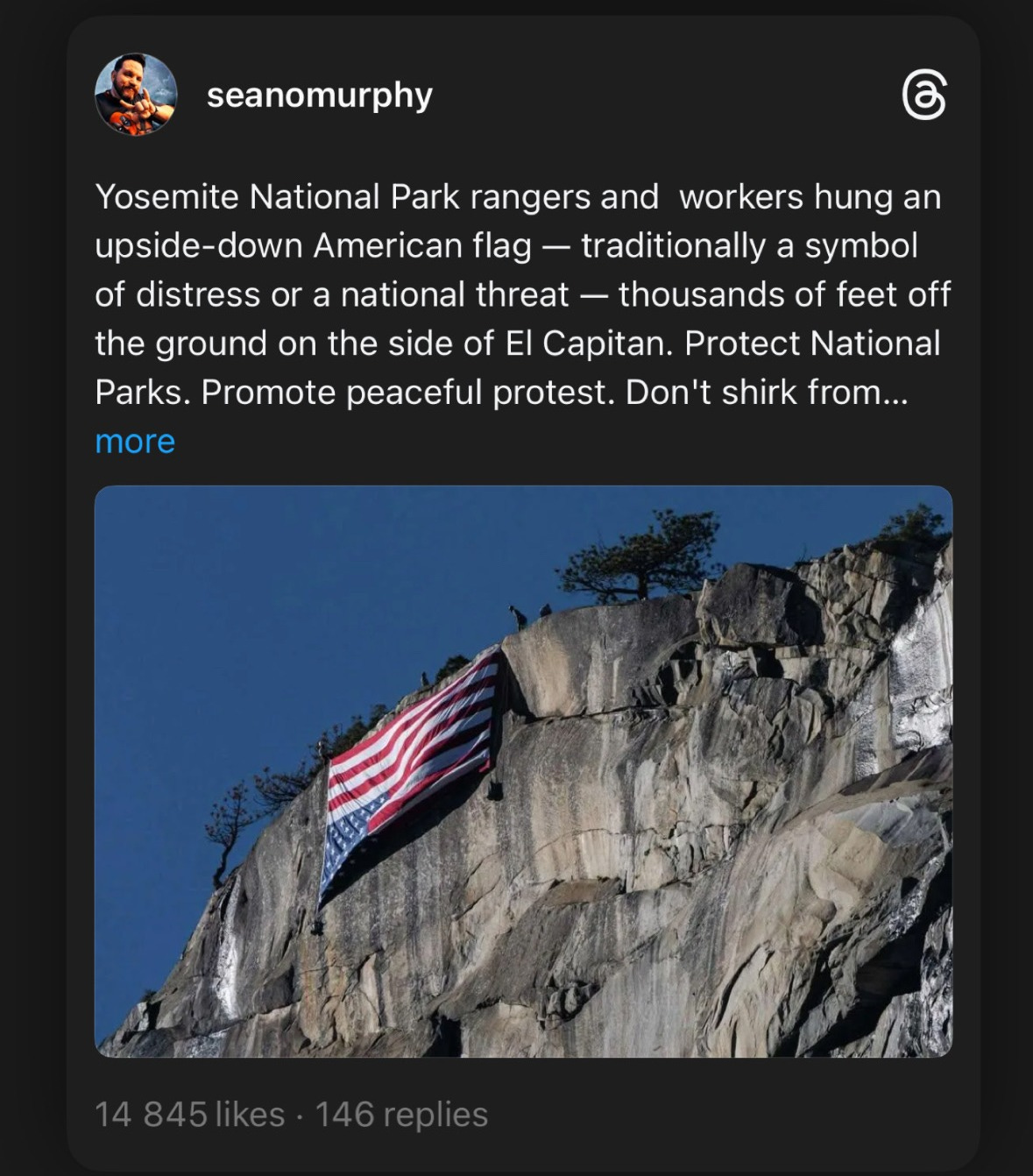

In case you missed it, 1,000 National Park Rangers and 3,400 employees of the US Forest Service were purged from the federal work force last week. These are the workers who clean your toilets, help you if you’re lost or injured, build your trails, offer your child’s Junior Ranger programs, manage forests and preserve wildlife habitats. Their stories have flooded my social media feed lately – and they’re heartbreaking.

This isn’t just about federal employees losing their livelihoods and, in many cases, their homes. It’s about access to the land that is ours. The park system was already chronically underfunded and after the firings, several sites have announced that they are cutting hours. What’s even worse, advocates for the park system fear that this is just the beginning of the end of public land in the US as we know it.

Deregulation and defunding

Already, multiple secretarial orders target some of America’s most pristine wilderness, threatening to open protected areas for energy exploration and production. The administration is also pushing to get rid of protections for wildlife and eliminate national monuments, some of which were established way back when Roosevelt was in office. This slash-and-burn approach to government and cutting of environmental regulations present an acute threat to our air, soil, water, climate and access to natural areas. And it may be the first step of a larger plan to sell out public lands to the highest bidder.

It's not in my nature to be alarmist, but I’d lie if I said I’m not extremely worried about the current development. As I walked around the American Natural History Museum in New York City a couple of days ago, learning about the legacy of Theodore Roosevelt, I also felt incredibly sad. Humans have such a fractured relationship with nature – our home – and we keep abusing it in the worst possible ways to quench our thirst for profit.

The power of taking a child outside

But feelings of sadness and hopelessness won’t save any public lands. Resistance will. If you’re American, contact your congress representatives and senators to voice your opinion. Follow the Alt National Park Service and share their posts. Speak up and educate others on the importance of having access to nature. Cut consumption. Donate to conservation organizations if you’re able to. And, keep taking your children outside, to nurture their sense of wonder and give them a chance to fall in love with the more-than-human world.

Because Roosevelt didn’t suddenly become a conservationist while walking the halls of the White House. He wasn’t moved to establish the US Forest Service and protect the Grand Canyon from behind his desk in the Oval Office. His environmental ethos was formed long before, while observing ant colonies and collecting plants and insects for his nature journal as a child. He became a conservationist while fly fishing the rivers of the American West, snowshoeing through the woods of New England and sleeping under the stars in California.

Taking a child outside and nurturing their sense of wonder may not be a quick fix to protect public lands. But it is a long-term vote for Mother Nature.

One thing to contemplate

“Leave it as it is. You can not improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it. What you can do is to keep it for your children, your children's children, and for all who come after you, as one of the great sights which every American if he can travel at all should see.”

- Theodore Roosevelt, making the case for protecting the Grand Canyon from development. He designated it a national monument in 1908.

Two things to read

1. Former ranger joins protests against the cuts to National Park Service. A first-hand account of what’s going on in the National Park Service and why the administration’s policies are detrimental to our shared natural heritage.

2. Our National Parks by John Muir. One of the most revered naturalists in US history, John Muir’s detailed observations of Yosemite, Yellowstone, and forest reservations of the West is as relevant today as it was over a hundred years ago.

Three things to do

1. Practice small acts of restoration. Plant a tree. Rewild a patch of land. Reduce light pollution in your neighborhood. Every act of restoration, no matter how small, is an act of resistance and defiance against destruction.

2. Tell new stories. The stories we tell shape the world we create. Instead of just warning about dystopias, tell stories of resilience, restoration, and reconnection with nature. Reclaim old myths, rewrite new ones, and help others see that we’re not doomed to the worst-case scenario.

3. Come together for a day of community work. In Norway, this is known as the dugnad and usually involves different improvement projects outdoors, like renovating a shelter in the local woods, preparing a community garden or cleaning up a natural area.

See you outside!

Linda

Some housekeeping…

If you can’t find my newsletter, check your spam folder. And please mark this address as ‘not spam.’ If the newsletter isn’t in your spam folder either, you should look in the Promotions tab.

You can always read my posts on my Substack home page.

You might also like…

Do not disturb, do not destroy

Finding freedom in nearby nature

Fear, ignorance and convenience are the enemies of outdoor recess

Why cities need more trees and less concrete

Before you go...

I have a curated selection of some of my favorite children's outerwear at Outdoor School Shop. When you shop through the link, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. Check out the Rain or Shine Mamma shop at ODSS here.

I've published two books: There's No Such Thing as Bad Weather and The Open-Air Life. If you enjoyed them, you can help others find them by leaving an Amazon review here and here respectively.

I often get interviewed about outdoor play and nature connection at various podcasts. You can find all the episodes I've participated in here.

Do you have a book club or head up a nature play community? I love doing virtual author visits! Just hit reply to this message to connect.

I do virtual speaking events for corporations, non-profits and online summits. You can read more about that here.

Do YOU have something going on in the nature connection space that you think this community should hear about? If so, hit 'reply' and let me know what you're up to - I'd be happy to share!

I appreciate this post, Linda. These are, indeed, scary and difficult times.

Thank you for the Wonderful Post!

Your time and efforts are greatly appreciated 🙏